2021 Annual Report:

During a four-decade career working in museums across the United States, Lonnie G. Bunch III has perceived an interesting gap in how museums have traditionally captured the history of the United States in exhibitions, collections and educational programs.

“I’ve asked myself, ‘Where can I learn about the complexity of spirituality and religion in America?’” recalls Bunch, who is secretary of the Smithsonian Institution based in Washington, D.C. “It was rarely there. Even though the notion of religion is important, cultural institutions have tended to shy away from it. They may mention it but with no deep understanding.”

Yet, he contends you can’t fully comprehend U.S. history or where the nation is headed without considering the role of religion. That’s why Bunch led the Smithsonian’s effort to create the Center for the Study of African American Religious Life, which was supported by a $10 million Endowment grant in 2015. It is based at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, where Bunch served as founding director.

Recognizing the important role religion plays in shaping American life, the Endowment is continuing to make grants to support the efforts of museums and to fund documentaries, public radio broadcasts and podcasts that strengthen the public’s understanding of religion. These grants are in addition to grants the Endowment has made that are helping Religion News Service and The Conversation U.S., in collaboration with The Associated Press, strengthen their news reporting about religion.

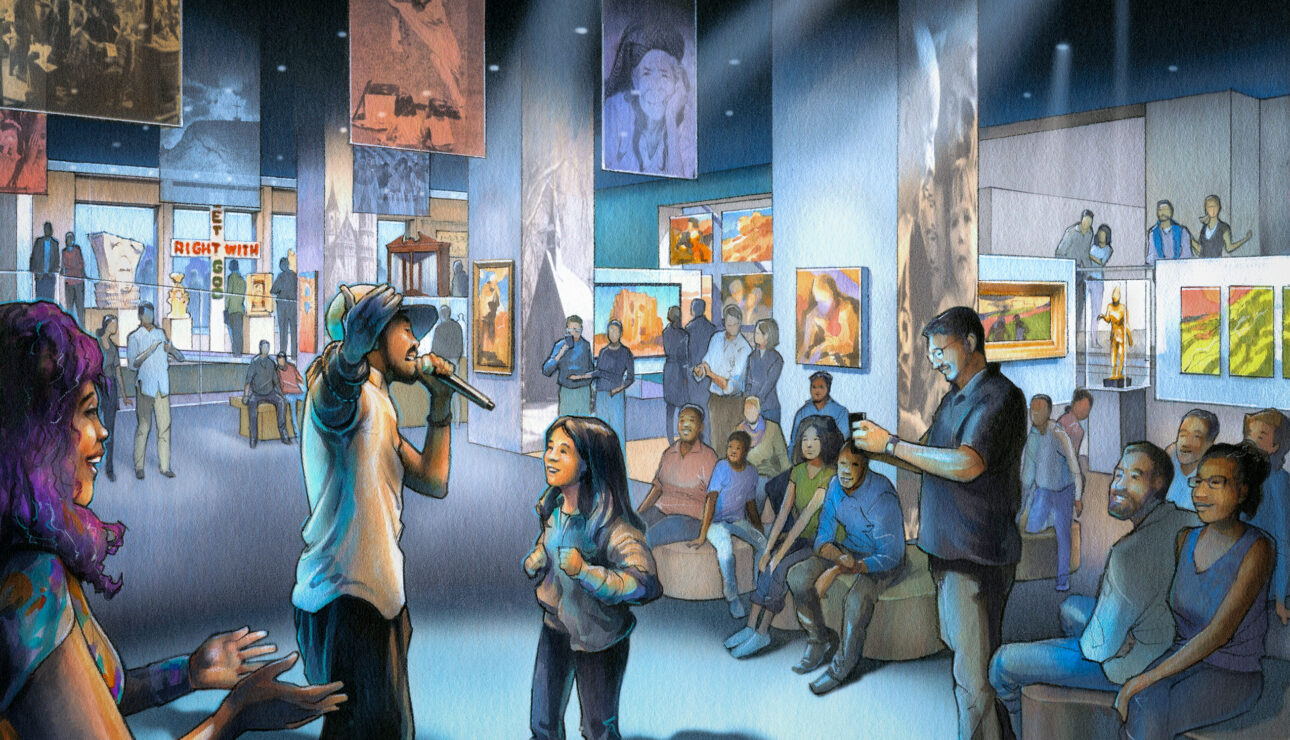

Exhibitions explore religion’s role in American culture

Through its Religion and Cultural Institutions Initiative, the Endowment asked museums to consider how an exploration of religion could help them further their missions. The initiative began with a series of planning grants in 2019, followed by grants totaling more than $43 million that are funding implementation of projects at 18 museums and historic sites around the nation. They include grants supporting efforts at four Smithsonian museums and cultural centers: The Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the National Museum of American History, the National Museum of African Art and the National Museum of Asian Art.

Funding has helped the Smithsonian establish a Center for the Understanding of Religion in American History and endow a curator in religion to run the center. Peter Manseau (left) now directs the center. As different Smithsonian museums explore the place of religion in their collections and exhibitions they are reflecting important perspectives on religion, Manseau says.

Funding has helped the Smithsonian establish a Center for the Understanding of Religion in American History and endow a curator in religion to run the center. Peter Manseau (left) now directs the center. As different Smithsonian museums explore the place of religion in their collections and exhibitions they are reflecting important perspectives on religion, Manseau says.

“American religion has been diverse from the very beginning; it has never been about one religious tradition or even several religious traditions,” he says. “It always has been about the interactions of many traditions.”

Manseau adds that religion is embedded throughout American culture, not restricted to houses of worship or personal religious practice. These are aspects that the Smithsonian is working to illuminate through its exhibitions and public programs.

“Lilly Endowment gave us the opportunity to take an area like religion, which can be considered controversial, and make it the key to understanding who we are as a people, who we are as a nation,” Bunch says. “It’s important to let people understand how, in many ways, religion has been a glue in America and then sometimes a hammer that divides.”

Encouraging new conversations about religion

Longtime journalist Krista Tippett (left) developed her own curiosity about the public’s perception of religion following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in America in 2001. “I was aware that the diversity within religious traditions had been lost in terms of a public imagination,” Tippett recalls. “There was one way to be religious. One way to be a Christian. One way to be Muslim. Those were the things I wanted to shine a light on.”

Longtime journalist Krista Tippett (left) developed her own curiosity about the public’s perception of religion following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in America in 2001. “I was aware that the diversity within religious traditions had been lost in terms of a public imagination,” Tippett recalls. “There was one way to be religious. One way to be a Christian. One way to be Muslim. Those were the things I wanted to shine a light on.”

When Tippett proposed a religious-themed program for public radio in 2003, the idea was met with trepidation.

“It was very controversial to talk about religion on public radio,” she says. “There were a lot of skeptics. I just had to do it and show that it didn’t have to fulfill everybody’s worst imagination. It didn’t have to be proselytizing. And, yes, it could be intelligent. It wouldn’t necessarily make everybody angry or feel exclusionary.”

The result of that effort is “On Being,” a multi-media project that began as a one-hour weekly public radio show. It has aired on more than 400 public radio stations each week, and podcasts of the show have been downloaded more than 300 million times. Tippett has plans eventually to end the public radio show and focus “On Being” more on podcasts and other digital media formats.

Through “On Being,” Tippett explores the human condition through conversations with guests that cover topics such as grief, healing, beauty, loneliness, fear, eternity and goodness. Guests have ranged from theologians and clergy to scientists and researchers, including the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the primatologist Jane Goodall, Franciscan Catholic priest Richard Rohr and Rabbi Sandy Sasso.

The Endowment’s support for “On Being” and other efforts that help strengthen public understanding of religion reflects a recognition that people are increasingly interested in engaging with religious and spiritual ideas and questions outside of traditional religious institutions.

“This idea that it has to be a certain way and everybody turns up at a certain time in a certain place to practice religion is not the case anymore,” Tippett says. “This change is not just happening to religion; it’s happening to all our institutions. The church and other organizations are all included in this cultural paradigm shift, and it really has been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Yet, religious and spiritual traditions offer valuable context to contemporary inquiry. That’s why a recent grant to support “On Being” is helping the organization integrate the voices of more theologians into its content.

Searching for answers to life’s hard questions

Kate Bowler (right), a historian of Christianity at Duke Divinity, has developed a podcast that is inviting audiences to explore their own spiritual and religious journeys. Called “Everything Happens,” the podcast grew out of her own deeply personal experience.

Kate Bowler (right), a historian of Christianity at Duke Divinity, has developed a podcast that is inviting audiences to explore their own spiritual and religious journeys. Called “Everything Happens,” the podcast grew out of her own deeply personal experience.

Bowler had spent much of her academic career researching the prosperity gospel in Christianity. But when she learned that she had life-threatening colon cancer at the age of 35, she began to step away from the objective, detached work of research and started asking questions that have altered her work and her faith life. Among the questions: “Was this meant for my life?” and “What does it mean to be a Christian in this world?”

“I used to be more of a belief-centered, idea-centered person, where I really appreciated Christianity for its very good arguments,” she says.

Since the diagnosis, which came after repeated attempts to get doctors to take her symptoms seriously, Bowler says, “I’ve needed so much love to hold my life together. I had a very powerful experience of God’s love when I felt largely disposable in a medical system that almost killed me.”

Since 2019, Endowment grants to Duke University have helped fund Bowler’s podcast. Named after her 2018 spiritual memoir “Everything Happens for a Reason (and Other Lies I’ve Loved),” it features Bowler’s conversations with cultural and religious figures that have included author Malcolm Gladwell, actor Matthew McConaughey, Episcopal Bishop Michael Curry, theologian Barbara Brown Taylor and Harvard University psychologist Susan David.

Bowler and her guests talk candidly about love, fear, uncertainty and loneliness—experiences that span people of all backgrounds, she notes. These conversations are especially needed today when people, she says, are looking for new ways to cope with challenges caused by the pandemic, social unrest and difficult personal circumstances. For many people, she adds, the old sources of comfort no longer work.

“We’re in the midst of an authenticity crisis, in which people are naturally quite skeptical of institutions and conventional leadership models,” Bowler contends. “People really want to hear the sometimes-messy wrestling with hard spiritual questions for which there often isn’t an obvious answer, and we have to find ways to stand in emotional intellectual traffic somewhere and be worthy of these conversations.”

Finding spiritual inspiration in the Black church

The Black church, which has served as a source of spiritual inspiration for Black Americans during incredibly difficult times, can serve as a source of comfort to all Americans, according to Harvard University scholar, filmmaker and author Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Gates (below), who directed the 2021 public television documentary “The Black Church: This is Our Story, This is Our Song,” says his work on the film further convinced him that the Black church has the potential to inform and fortify people of all faiths and backgrounds as they deal with difficult challenges.

“My biggest realization was that the Black church was a cultural laboratory,” Gates says of the project, which was largely funded by Lilly Endowment and produced by the public broadcasting station WETA in Washington, D.C.

“(The church) was the basis for economic institutions as it was the first self-sustaining institution funded by regular Black people with nickels, dimes and pennies,” he says. “And among the freemen and freedwomen in the South, the church was pivotal in terms of being an organizational center for Black reconstruction and ensuring Black men were able to vote.”

However, those lessons weren’t solely tied to financial and civil rights developments, Gates says. The well-received documentary, which debuted in February 2021 on PBS stations nationwide, also detailed the impact of the Black church in helping enslaved people and their descendants endure oppression. Watch the extended trailer.

“These people were picking cotton and being beaten and raped. Yet, they still held on to their belief in God, creating a culture of hope,” Gates says.

“I wanted to preserve a record of that—the complex legacy of the Black church.”

Even though the role of the church in the Black community has evolved—especially now that Black people organize and forge influence through many avenues within American society —the church remains a model for transformation in the nation right now, Gates says.

“All Americans need the essence of the Black church because we’re in a crisis. We’re terrified. Given the rise of white supremacy and COVID, people are looking for hope,” Gates says. “People are looking for the reassurance the church gave us. It gives us calm, assurance, confidence and peace of mind to deal with modern pressures.”

Gates is at work on a second documentary in conjunction with WETA. It will explore the impact of the Black preaching tradition and Black gospel music on American society. A $3.5 million Endowment grant to WETA in 2021 is supporting the project.

As the nation continues to grapple with formidable challenges, many will join Gates in finding comfort in the hope that religion has offered people across generations, Bunch says. Others will struggle to make sense of religion’s role because they are not part of a religious tradition or perhaps skeptical about faith matters. Yet Bunch contends that religion is important to the identities of all Americans because of who we are as a people. “As such,” he says “it’s something that needs to be explored in all its complexity.”

Religion and Cultural Institutions Initiative

Grants totaling more than $43 million are helping museums and other cultural institutions across the United States develop exhibitions and educational programs that fairly and accurately portray the role of religion in the U.S. and around the world. The Smithsonian Institution received grants to support efforts at three of its museums and one of its cultural centers and to enable the National Museum of American History to establish its Center or the Understanding of Religion in American History.

“The Black Church”

In 2018, the Endowment made a $3 million grant to WETA (Greater Washington Educational Telecommunications Association) to support “The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song,” a four-hour public television documentary first broadcast in February 2021. It traces the 400-year story of the Black church in America. A $3.5 million grant in 2021 is supporting a follow-up documentary that will explore the contributions of Black preaching and Black gospel music to American society.

“On Being”

Since 2004, Endowment grants have supported “On Being,” a radio show and podcast that originated at Minnesota Public Radio and is now produced through The On Being Project. A $2 million grant in 2019 enabled the project to continue its weekly broadcasts and podcasts, expand theological content and strengthen its engagement with Christian congregations and other faith communities nationwide.

“Everything Happens with Kate Bowler”

Duke University has received grants in 2019 ($649,021) and in 2021 ($1.1 million) to support Duke Divinity School professor Kate Bowler and her colleagues as they produce the podcast, “Everything Happens with Kate Bowler.” The podcast is part of a larger multimedia project designed to help people draw more fully on the

wisdom of Christian traditions as they face questions about faith, God, hope and suffering and how to live in the midst of uncertainty.